Raya and the Last Dragon | Review

Any time there’s a new major film that aims to represent an underrepresented group, there is breath-holding, fingers being crossed, a collective hope for said film to be no less than great. “It must be good,” we say, or else Hollywood will take it as a sign stories like these are not marketable and worth telling. There’s also a tendency to treat these films as the definitive representation of these communities. These opportunities are still, unfortunately, so rare in Hollywood that we have to take what we can get and hope the films do justice by these communities. Raya and the Last Dragon is the latest such film, featuring Disney’s first Southeast Asian princess. Does the film reach these two lofty expectations? Yes and no. It’s a great film, thankfully, but it does not, and cannot, be the definitive story of the Southeast Asian community—we are too large and diverse for any one film to be that.

Raya is set in the fictional land of Kumandra, whose geography is shaped like a dragon. Kumandra used to be a prosperous world where humans and dragons lived in harmony until, 500 years ago, a mysterious plague called the Druun suddenly appeared and ravaged the world, turning everyone in its path into stone. The last dragons to stand against the Druun used all their magic to create the Dragon Gem, which eliminated the Druun and revived all of the humans, but as a result, the dragons turned into stone themselves. With the loss of the dragons so came the loss of trust among the people of Kumandra, and they splintered into five warring tribes: Fang, Heart, Talon, Spine, and Tail.

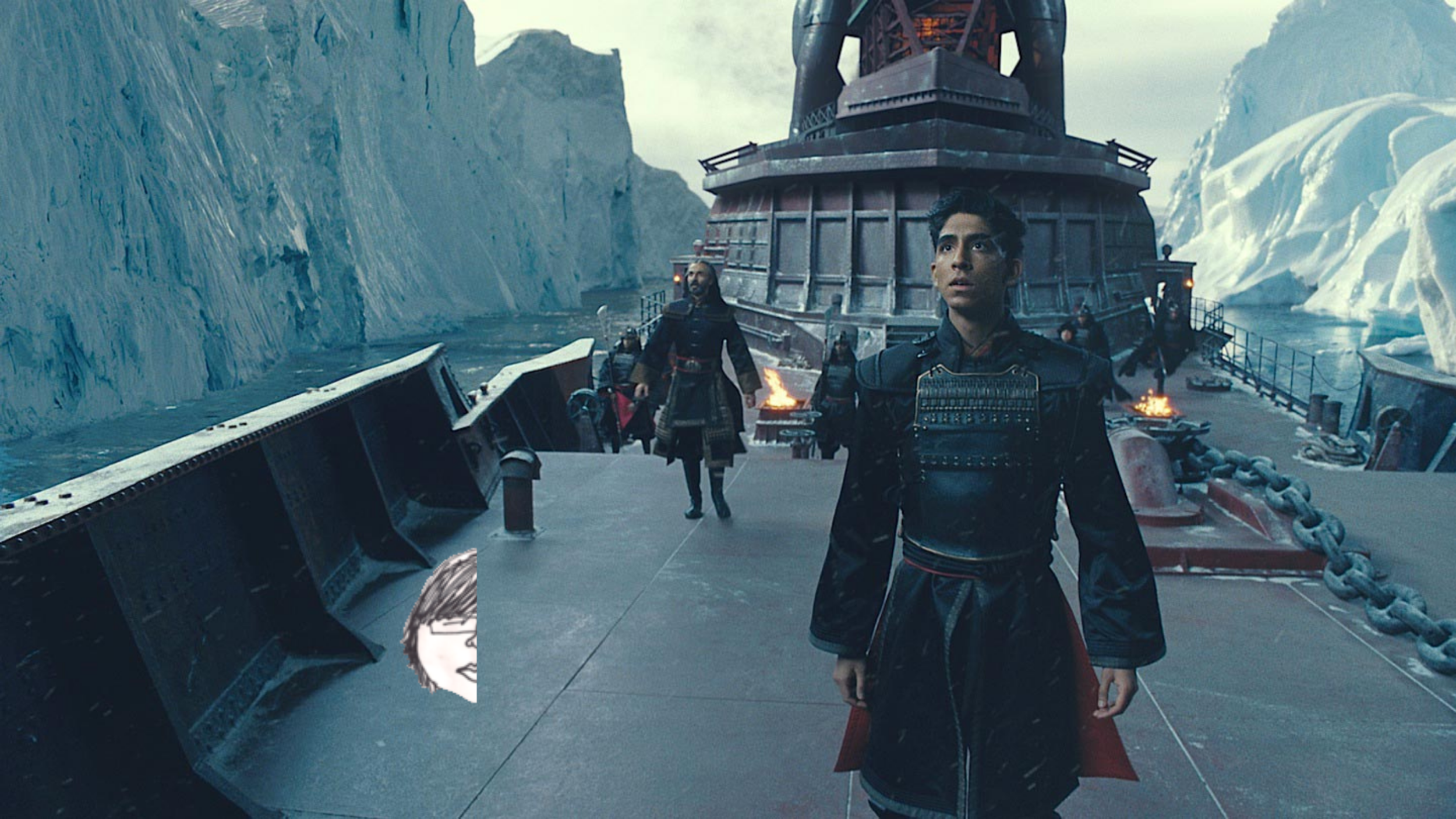

In the present day, the Druun have returned after the warring factions accidentally broke the Dragon Gem. Princess Raya (voiced by Kelly Marie Tran) of the Heart land must journey across Kumandra to find Sisu, the mythical “last dragon” who had apparently survived the battle with the Druun centuries ago but disappeared. Her goal is to reunite all five pieces of the Dragon Gem with Sisu so the world can be restored, but mostly so she can be reunited with her father, Chief Benja (Daniel Dae Kim), who was turned into stone. Along the way, Raya forms a rag-tag team of individuals who’ve also lost loved ones to the Druun, while also having to fend off against her childhood friend-turned-enemy Princess Namaari of Fang (Gemma Chan).

In this new Disney Renaissance era (Wreck-It Ralph, Frozen, Big Hero 6, Zootopia, Moana), there’s been a concerted effort by the studio to transcend what a Disney film can be. Yes, the formula still features cute sidekicks (human or animal, or both), new worlds to explore, and a buddy (two leads) or ensemble. But these later films from Disney Animation Studios have explored more ambitious themes, even if they’re not always successful, including sisterhood, grief, toxic friendships, and even racism, reparations, and colonialism. Raya follows this trend by centering around its major theme of trust, something Kumandra, and our real-life world, can use more of. Trust is something Raya lacks, ever since a personal betrayal led to the destruction of the Dragon Gem, the return of the Druun, and the loss of her father. It’s the lack of trust that led to the infighting between Kumandra’s people in the first place. Regaining her ability to trust others, and the world around her, is a major aspect in Raya’s journey worth commending, even though the film doesn’t execute this theme as strongly or as emotionally as, say, the scene from Finding Nemo when Marlon finally learns to trust his son. But like I always say, I’d rather a film aim high than settle for something easy.

There’s a lot to like about Raya. On a technical level, the score from James Newton Howard (The Dark Knight & The Hunger Games) features some memorable tracks (I like “Fleeing from Tail,” “Sisu Swims,” and “The New World”). The animation is gorgeous and stunning, which is no surprise coming from Disney. But what is surprising is how the film is anchored by three female characters—Raya, Sisu, and Nimaari—yet they all have distinct facial features (Sisu turns into a human at one point in the film, in case you’re confused why I’m comparing the face of a dragon to a human). Considering how much previous Disney princesses look alike (more recently, Anna, Elsa, and Rapunzel), it’s especially noteworthy that the creative team have put effort in making Raya’s characters have their own unique features, especially when the Asian community is often stereotyped as looking all alike. And all of the directors and writers deserve credit for keeping everything together and presenting a coherent and thrilling film despite production issues, including directorial and acting replacements. Despite running 107 minutes, the film zips by at a steady pace, leaving me wanting to spend more time in the world of Kumandra and its many lands. I also wish it were a musical, like all of the other Disney princess films before it, not only because I love musicals, but because it would’ve been a great way to avoid some of the film’s heavy exposition.

I appreciate the fact that each member of Raya’s group, including baby con artist (yes, you read that right) Little Noi (Thalia Tran), pre-teen entrepreneur Boun (Izaac Wang), and giant warrior Tong (Benedict Wong), represents each of Kumandra’s five lands without ever calling attention to it. It’s beautiful to see these diverse characters finding one another and forming their own little chosen family. I love the kick-ass action the film features, mostly between Raya and Nimaari, showcasing various forms of Southeast Asian martial arts, including Indonesia’s Pencak Silat, Thailand’s Muay Thai, and the Philippines’ Arnis. And I like that Raya, whose voice actress is Vietnamese-American, calls her father “Ba,” a word I, like many other Vietnamese-Americans, call my own dad. It’s minor, but it’s an example of how these culturally-specific aspects of a story, things that other audiences wouldn’t notice, can be meaningful to a community begging to be seen.

Admittedly, I’m not someone who really cares that much about Asian representation in media. I still appreciate it, and I’ll still share posts on social media to support further representation of Asian Americans, but in the grand scheme of things it’s lower on the list of priorities to dismantle white supremacy. But I’m also not one to downplay the importance representation does have and its impact on viewers. I’ve seen people literally cry tears of joy seeing themselves in this film. It clearly means something to a lot of folks. And simply from a creative standpoint, this kind of representation offers a breath of fresh air in the sea of homogenous stories from Hollywood.

And speaking of representation, that’s a department Disney still needs improvement on, despite starring Disney’s first Southeast Asian princess. Regarding Disney’s decision to create a world inspired by Southeast Asian cultures as a collective, instead of a specific Southeast Asian one, I can understand why. From a creative standpoint, it’s much easier for your story to be “inspired” by many cultures instead of being constrained by cultural specificity. After all, even within the Southeast Asian community it’s wildly diverse (Burmese, Cambodian, Filipino, Hmong, Indonesian, Laotian, and more). But the downside of combining all of these diverse cultures into one is that it can dilute their impact. I knew going into my first viewing of Raya that the film was inspired by many Southeast Asian cultures. During my viewing, I was able to recognize some Vietnamese references, but other times I was left wondering if certain things were from actual Southeast Asian cultures or if they were just made up for the film with no cultural basis. For example, the word “Binturi” is thrown around a lot in the film, but I didn’t know if it’s a real word or made up. This leads to sort of oriental or exotic view of Kumandra, one where anything that sounds strange is Asian, that would’ve been avoided had it been inspired by a specific country. Why is it that Disney has been able to offer culturally-specific films in the past, including Beauty and the Beast or Ratatouille (France), Coco (Mexico), and this year’s Luca (Italy), but when it comes to films inspired by Asian or Pacific Islander cultures, like Aladdin or Moana, they’re a hodgepodge of several different ones? Yes, there’s Mulan (there’s always an exception to a rule) but, then again, that film was notoriously ridiculed by China for not even being culturally accurate.

It’s already easy enough for non-Asian people to mistake one Asian culture for another on the basis of how we look. Yet the Asian racial group is one of the largest and most diverse, not only divided into East Asian, Southeast Asian, South Asian, and more, but even more subgroups within each of those subgroups. Heck, I didn’t even know there were these subgroups of Asians until college! Growing up in a predominantly white community, the only other Asian people I knew were Vietnamese. I didn’t know Vietnamese people were specifically Southeast Asian, so I definitely didn’t know what it meant to be East Asian or South Asian. And there are signs maybe even Disney’s own leadership doesn’t understand the differences between these Asian subgroups.

Awkwafina, Gemma Chan, Daniel Dae Kim, Benedict Wong, Sandra Oh, Lucille Song—what do all of these actors have in common? They’re all East Asian. And they make up the majority (majority!) of the cast of Raya, a film inspired by Southeast Asia. Even the film’s main credits song is from an artist of East Asian descent (Jhené Aiko). That’s a pretty galling oversight on Disney’s part. At best, they didn’t know there was a difference. At worst, they did know but didn’t care. It’s a huge disappointment that probably could have been avoided had the film’s directors been at least Asian. There are four credited directors for the film, a result of a creative overhaul that took place almost a year before the film’s release—three are white (Don Hall, director of Big Hero 6 and Moana; Paul Briggs, head of story on films like Frozen and Big Hero 6; and John Ripa, story lead on Zootopia), and the fourth is Mexican (Carlos López Estrada, director/writer of Blindspotting). Unfortunately, this isn’t new when it comes to Disney. Before Raya, there hasn’t been a single film from Walt Disney Animation Studios directed by a person of color. In its 84 year history (from my knowledge, Pixote Hunt is a Black director who worked on Fantasia 2000 but that film is composed of various segments, each directed by a different person)! And sister studio Pixar is only just now getting to that, with last year’s Soul being their first film written and directed by a Black person. Before Soul, the only Pixar films directed by non-white people were 2015’s The Good Dinosaur (Peter Sohn) and 2017’s Coco (co-directed by Adrian Molina). Next year’s Turning Red will be from Pixar’s first woman of color, Asian, and Asian woman director, Domee Shi. Clearly, there’s a lot of work to do.

Raya’s saving grace is the foundation laid out by the film’s screenwriters Qui Nguyen (Vietgone) and Adele Lim (Crazy Rich Asians), both of whom are of Southeast Asian descent (Vietnamese and Malaysian, respectively). It’s through their knowledge and lived experiences, as well as those of the film’s Southeast Asia Story Trust and consultants, that Raya maintains its culturally-specific aspects, like the aforementioned martial arts, words like “Ba’ and “Dep La,” and even the food.

In the end, Raya and the Last Dragon is a rousing and entertaining adventure worth spending time with. It’s largely a return-to-form for the studio after the semi-disappointing, though equally-ambitious Ralph Breaks the Internet and Frozen II. And Raya features not one, but two smart, brave, badass (possibly even gay) Southeast Asian princesses that a new generation of kids can admire and look up to. And the film’s themes are as timely as ever (coincidentally, the Druun are referred to as a “plague”), supporting the idea that mutual trust can save the world, if we only worked together for the greater good. In a time when anti-Asian hate crimes are soaring in real life, it’s sort of radical to see a mainstream story featuring Asian heroes saving the world.